Moving Information Across Boundaries

In this two-part series, I will be borrowing from the presentation I gave at the Information Architecture Conference earlier this year: Moving Information Across Boundaries, Information Theory for Information Architecture.

This series is derived from my IAC presentation, but slightly altered to focus on the role of information architecture in addressing an organization’s foundational challenges. Part one introduces the key components of information theory: Message, Channel, and Boundaries. Part two will go deeper into the direct impact this approach can have on large scale information rich projects.

First, we need to create some context around information architecture and information theory. Starting with the assumption that the goal of information architecture is to move information from one place to another.

This assumption provides two important insights:

- It helps focus on the task at hand, allowing organizations to dig into the roles that information plays.

- Second, it clarifies that the value of information is realized when it is shared.

It requires effort (time, money, processes) to move anything, including information. This puts the onus on information architects to ensure that we understand how information is going to be used, how the recipients of the information are going to interact with it, and what the value of the information is to the organization.

A Mathematical Theory of Communication

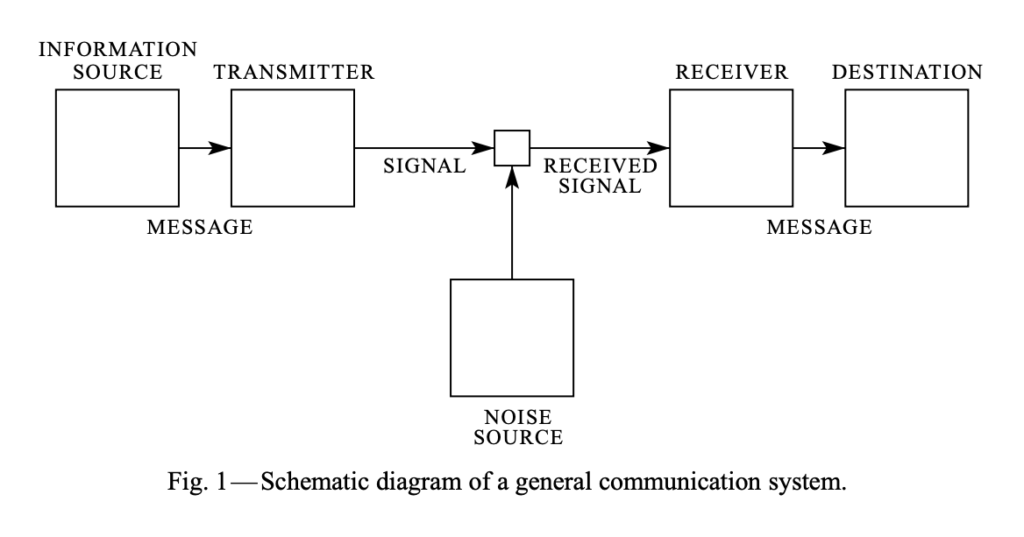

At the start of A MATHEMATICAL THEORY OF COMMUNICATION, Claude Shannon wrote, “The fundamental problem of communication is that of reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a message selected at another point.” To be transparent, he was focusing exclusively on the transference of digital signals in the form of “bits” (a term he coined), was approaching this as an electrical engineering problem, and his notion of information was definitely more abstract than what we generally wrestle with, but the impact of his work has been profound. Almost every device (certainly every digital device) that transmits and or receives information is dependent on the field of information theory. Including cryptography and cell phones. Let’s look at how Shannon looked at information and communication.

Information & Communication

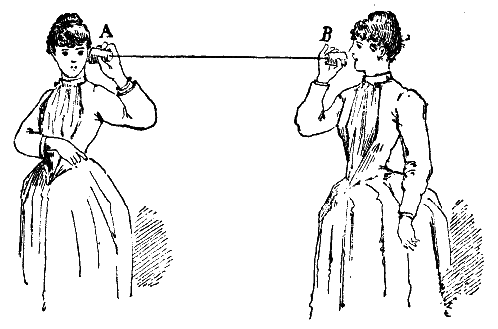

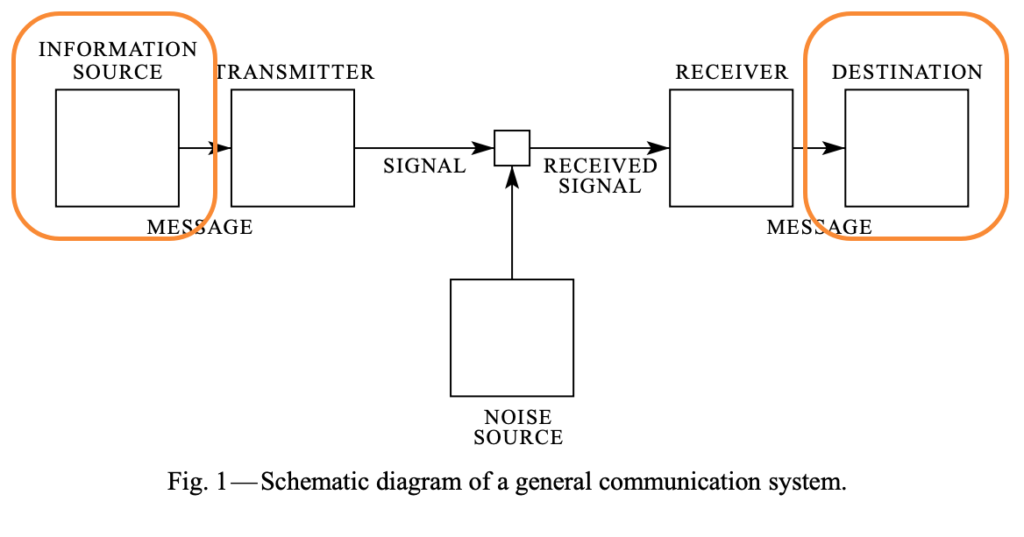

Looking at this diagram, the notion of a sender, transmitter (encoding), the modality of transmission, a receiver, and a destination are all directly in play. Given that the primary goal of IA is to transfer information (not data) from one place to another, this serves as an excellent starting point. It’s safe to say that any IA project puts these components in play, even if they are not called out explicitly.

For our purposes, we will use the notions of the sender/receiver, channel, and boundaries. All of these have had direct implications in Factor’s work and provide a valuable frame for the development of our robust methodology. It should be noted that effort (energy) needs to be added to the system to move the information. This framework informs our understanding of where to best place our efforts or energy.

Can you identify the Sender/Receiver, Channel, and Boundaries in your organization’s information architecture needs?

Sender / Receiver

The goal here is to get information from the source to the destination. To do this well we need to understand as much as we can about each. Because the source and destination are generally people (although not always), we need to know their information needs, their context, what they already know, etc. Knowing this helps us understand what information to send both in terms of content and structure. For example, if we know the receiver speaks English and Hindi, then we know we need to send the message in one of those two languages…or we need to provide a process to translate it into one of those two languages.

Implications for Organization, this provides the focus for user research, competitor analysis, and, to some extent, internal processes. Focusing on the information goals, perspectives, and context shared by the sender and receiver will inform the amount, format, and type of information that needs to be shared.

There are often multiple senders and receivers in an enterprise’s information architecture: customers, employees, investors, media, and more.

Channel

Though these should really be broken up into their discrete portions, we can refer to the bordered area as the channel. This is the process and infrastructure for encoding a message, sending it over a “wire” and then decoding it for the receiver. The wire in this case can be an actual copper wire, fiber optic cable, radio channels, etc. It could be a website interface or physical space.

This wire (or channel) has a transmission limit (how much information can be transmitted) and is where noise may enter the system. Increasing the transmission limit or reducing the noise are both things that we address in our work at Factor. For this reason, the work we do to understand the full context of the communication is essential, leads to unexpected places, and often results in fundamental organizational change.

Can you identify your organization’s channels based on the goals for your IA?

Cape Spencer: “It’s high tide. Time to check email.”

This is a picture of the Cape Spencer lighthouse in Southeast Alaska where I’ve done a significant amount of paddling amongst the islands. I visited some friends who are in the commercial fishing business. They kept their boat in a cove when they weren’t fishing that was about three or four miles from this lighthouse. And at one point during my visit, my friend said, “Oh, it’s high tide, we need to check our email.” Because at high tide my friends had line of sight to Cape Spencer, which was required to access the cell phone tower with 3G connectivity. Their channel only worked at high tide.

Implications for Organization, this illustrates the importance of understanding as much of the information context as possible. To be honest, at Factor, we have never looked at the tidal cycle for our work, but seemingly equally orthogonal issues have had huge impacts on the solutions we design: organizational structure, job descriptions and compensation plans, brand guidelines, and even long standing feuds between VPs, have all impacted our solutions and recommendations.

Boundaries

One way to think about boundaries is that the information is crossing a boundary when it moves from one place to another. Factor helps identify and understand these boundaries, and how they impact information, the channel, and the senders/receivers. If our work is going to allow information to move from one place to another we need to determine the best way to package it up and send it. We need to best understand the context of the information being delivered.

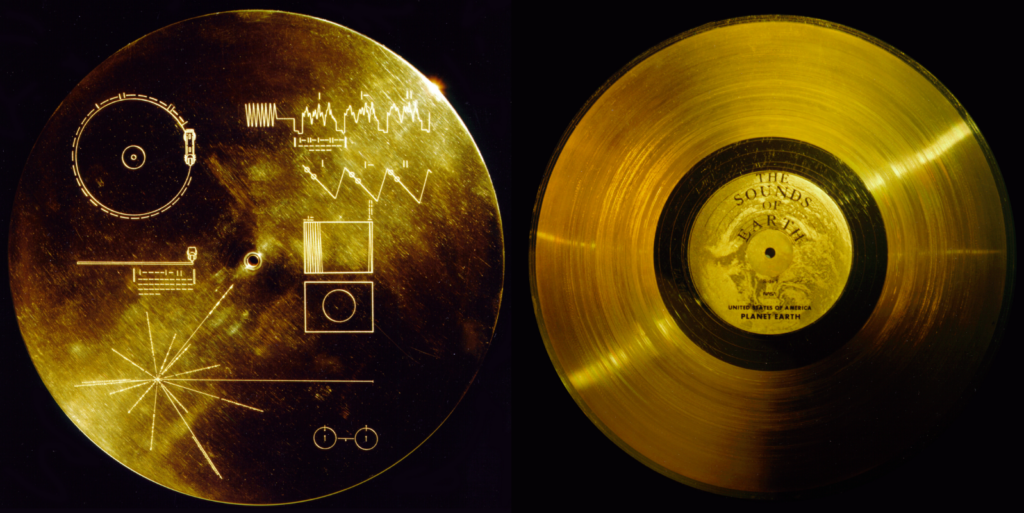

An extreme example of crossing boundaries and not knowing very much about the receiver is the Voyager Golden Record. In this case the only thing that could be done was to make assumptions about the receiver. More common boundaries include moving information across technical systems, business units, languages, interfaces, etc.

Paul Revere

So, before we move on to Part 2, let’s look at a famous event in American History, Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride, as a showcase example of information theory and moving information across a boundary.

- Sender and Receiver: agreed upon the domain and potential set of messages; “one if by sea and two if by land”. And, most importantly they knew what to do with that information (similar to librarians agreeing to a classification scheme).

- Channel: Senders and Receivers were able to choose the best channel with the right amount of capacity. Because the sender and receiver had already agreed upon the domain and extent of information that needed two lanterns in the evening where all that was required.

- Boundary: Knowing the Boundary allowed them to take advantage of it: Evening so the lanterns could be seen and distance

| Information Theory | Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride |

| Alignment between sender and receiver | Both knew exactly what needed to be communicated |

| Understanding the domain of the message | “One if by land… two if by sea” |

| Channel and its capacity | Line of sight – two lanterns |

| Boundary | Evening, Charles River |

With this basic understanding of information theory and the basic challenges involved in getting information from one location to another, we’ll take a deeper look at the implication for IA practitioners in Part 2.